An experimental drug from AstraZeneca succeeded in a late-stage trial in an autoimmune condition called generalized myasthenia gravis, positioning the company to grow a business it inherited when acquiring Alexion Pharmaceuticals five years ago.

The drug, known as gefurulimab, met its main and secondary objectives in a Phase 3 study involving 260 people with the condition, AstraZeneca said Thursday. The company didn’t provide specifics, but said that, when compared to a placebo group, treated study participants experienced a “statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement” after 26 weeks, as measured by a change in scores on a questionnaire commonly used to assess disease symptoms.

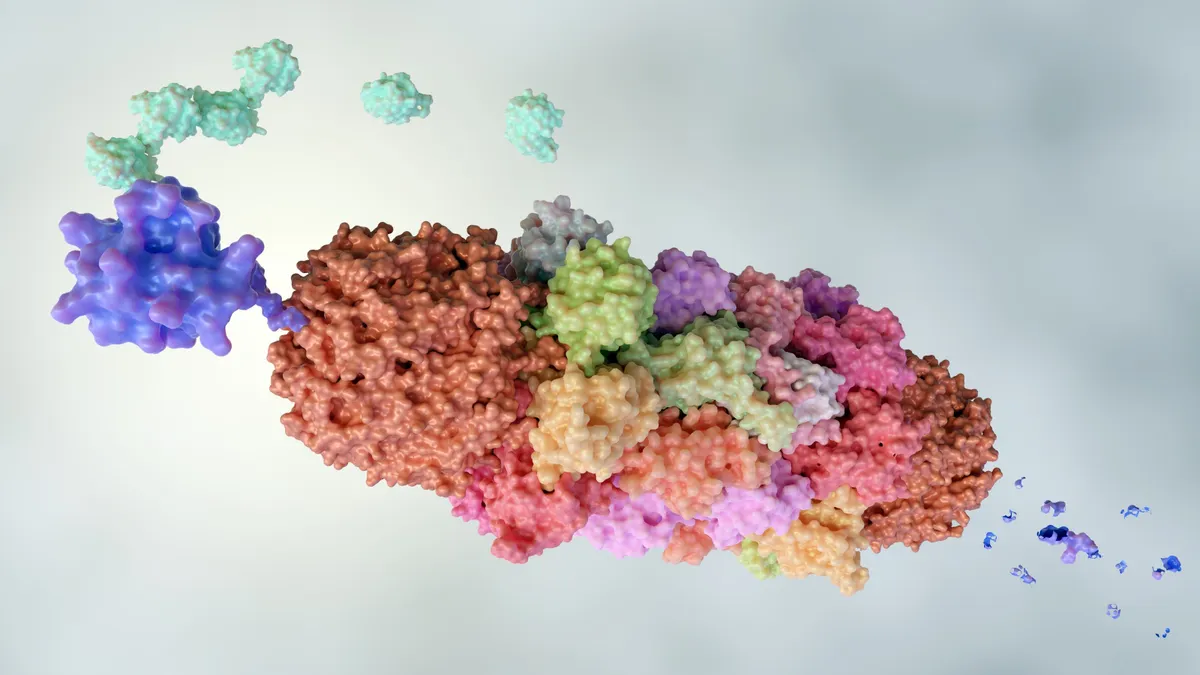

AstraZeneca added that its drug was well-tolerated and showed a safety profile consistent with previous studies of therapies like gefurulimab, which are known as C5 inhibitors. The company will present detailed results at a future medical meeting and share them with global health regulators.

The findings give AstraZeneca the chance to bulk up a rare disease business acquired through the nearly $40 billion purchase of Alexion in 2020. That business is headlined by two products, Soliris and Ultomiris, and has grown steadily, generating nearly $9 billion in sales last year. AstraZeneca sees Alexion’s assets as essential to reaching a goal of $80 billion in annual sales by the end of the decade — and gefurulimab, which originated within Alexion, is one of the drugs that can help.

Generalized myasthenia gravis is a rare and chronic autoimmune condition characterized by a range of symptoms that includes muscle weakness, fatigue, changes in vision and difficulty breathing. The Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America estimates 37 out of every 100,000 people in the U.S. have the disease, which impedes signals between nerves and muscles.

In an investor presentation last year, AstraZeneca predicted the market opportunity for generalized myasthenia gravis treatments will grow substantially in the future, as more patients switch from generic medications that manage symptoms to newer, branded therapies.

Accordingly, the disease has become a competitive area among drugmakers. Alongside Soliris and Ultomiris, newer medicines from Argenx, UCB and Johnson & Johnson, which work differently, have recently reached market. Companies developing B cell-depleting cell therapies and antibody medicines are advancing potential programs, too.

Like Soliris and Ultomiris, gefurulimab targets a part of the immune system known as the complement system. But unlike those medicines, gefurulimab can be self-administered weekly through an under-the-skin injection, rather than given through an intravenous infusion in a healthcare facility. AstraZeneca has said the drug could represent a way to reach a broader group of patients earlier in their disease.

“A once-weekly, self-administered C5 treatment option would offer patients greater convenience and independence in managing their condition, empowering them to have more control over their therapy,” said study investigator Kelly Gwathmey, an associate professor of neurology and chief of Virginia Commonwealth University’s neuromuscular division, in a statement provided by AstraZeneca.